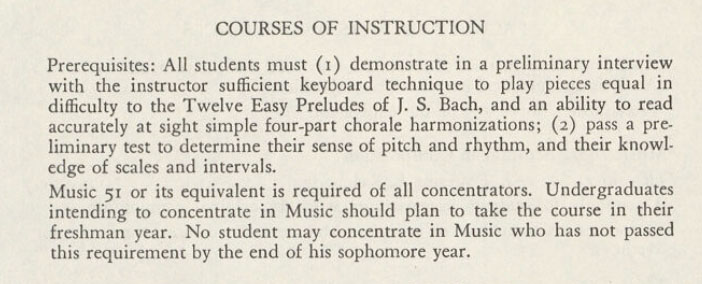

I wanted to concentrate in music in college. At that time, things were old-school and formal. The prerequisites from the course catalog are still etched in my mind, daunting and forbidding. They included an ability to sight-read four-part chorale harmonizations, and to play preludes of J.S. Bach. Alas, I had no piano experience at all.

In those early years, it did not occur to me to question what it said in black and white in the catalog. I should have, especially because a roommate was the son of the Music Department Chair. Looking back at it, I shake my head and say to myself, it might have been.

Well, who knows what that might have been like. I had no idea of what a career in music might be… weddings and bar-mitzvahs, perhaps. Then again, I read recently Li due Orfei: da Poliziano a Monteverdi, by my friend's father, and felt, I could have been very happy in the profession of music scholar.

But it turns out that life is long enough for more than one thing, and music is the delight of my life in retirement.

This carol dates back at least to the 1300s and is still sung to this day. Composers have made an amazing number of arrangements of it. Some of them, like this one, are quite free.

My playing has some slips and hesitations, and the tempo is slower than I would like. But one of the pleasures of retirement for me has been that I don't need to be competitive at things any longer, but can just do things because I like doing them. That is sweet rejoicing! I hope you will agree with the spirit.

I have been intrigued with the work of Heino Eller, an Estonian composer. His music is quite innovative without being strident or defiant simply for the sake of being defiant. Much of it is based on Estonian folk music, which unfortunately I have not been able to learn much about. He has harmonies that bring to mind the complex chords of jazz, though I believe predate those. Often his music is modal, like that of very early church settings, rather than simply major or minor. His rhythms are free, sometimes insisting on ending phrases on the last beat of a measure, rather than the first – a decided break from the pattern of finishing on the first, strong beat of the bar.

I have a particular interest in the period when Western music evolved to add an increasingly harmonic dimension to its polyphonic one. Roughly, this was from the late Renaissance to the early Baroque. The new twist was that dissonant intervals became part of the texture, driving forward until their resolution to repose in consonant chords.

Orlando Gibbons was a noted figure in the evolution of harmonic structures. The middle of this piece contains the first instance I know of with a strong, shaping V7 chord, a mainstay of Western music for the next four centuries.

This Fancy – Fantasy – could be and probably was played on a variety of keyboard instruments. It is particularly well-suited for organ because that instrument can sustain the voices of its dense, complex texture.

As always, I am conscious of the shortcomings of my playing. I offer it here as a fair example of what I can do, which I only wish will improve with time.

Franz Liszt's late music was full of exploration. His Elegy No. 2, composed in 1877, begins in a section without key signature, a lingering dirge that shifts by semitones through various harmonies. Initially, it has strong implications of F minor. After a page, though still written without key signature, it is recognizably in the (usually theoretical) key of Fb major. Some peregrinations later, the initial theme appears in Ab, the relative major, with the mourning transformed into a hymn of love.

Altogether, a very mystical, haunting, and ultimately beautiful experience.

This selection from the Songs without Words is the second of the musical videos I will post here. Like the first, it has artistic and techical shortfalls that I am only too aware of.

For the moment, I suppose that I am a child with a new toy. It is very good one, though. I expect that I will refine this page as new entries come, and that it will become more selective, like those of my art and reading.

I have continued to be intrigued by the puzzle of the hands moving far earlier and faster than the brain can follow them.

The Economist of August 29, 2020 notes –

The way that humans walk is sometimes described by biomechanists as controlled falling. Making a stride involves swinging a leg out and placing it down with small subconscious corrections to maintain stability as the mass of the body above it shifts foreward. Each leg works like a spring.

That is a good description of fingers landing on the keys. They head out as quickly and in the best direction that they can. Somehow or the other, before one becomes aware of it, they have felt the surface beneath them and adjusted their final course. It is a mystical process, if one's analysis focuses on awareness – but awareness seems to come long after the fact, when the fingers are playing any number of notes per second.

Learning to play the piano is pretty much an inch-by-inch affair, with magic moments very few and far in between. One such moment recently came when I set out to learn to play octaves, a standard piece of technique that somehow din't make it into my years of lessons. I found an internet post (which unfortunately I can't lay my hands on right now, since I would like to ascribe proper credit) suggesting that before playing the notes, one should locate them by feel with the fingertips. I haven't mastered octaves yet by any means, but this approach turns out to be extremely fruitful overall, not just for octaves.

I noted long ago that of all the mistakes a pianist makes, hitting between two notes, and so playing both of them at the same time inadvertently, is extremely rare. I believe that the pianist conditions himself to feel the cracks between the keys, with the fingertips figuring it out long before any conscious feeling of a separation occurs, if indeed it occurs at all. If you watch a good pianist play, you will notice him continually reaching for and feeling out notes quite a bit before it's time to play them. (Of course, sometimes there just isn't time for such things, so full technique includes being able to make big leaps in almost less than no time.) A violinist, for instance, needs to come at things differently because there is nothing to feel about the notes; he has to hear them and rely on proprioception.

I think that, most of the time, playing a piano note involves a couple of stages. Usually, the first is feeling that the key is there. If you're expecting to put your foot, or finger, down on something firm, and it turns out there's a void then and there – the reflexes instantly say, "Oopsie! I need to let my friends know about this, and maybe even report it to the brain" – triggering consciousness. Meanwhile, motion tends to freeze up, and the muscles tense up because the hand knows it's supposed to be doing something, but it doesn't know what. It doesn't want to descend into an abyss. Tension makes things much, much more difficult. I have found that practicing for feel also is very conducive to building smooth motions. The next finger needs to be close to in place before the current finger does its thing. As one of my teachers remarked, it gets easier as it goes along – or so it should.

After my mother died, I estimated that it would take me about two years to bring my piano technique back to where it had been at its top. That was about right. The question now, of course, is improvement from here…

It has been marvellous to have a fresh start with the piano, as with the rest of my life. Practice as repetition by itself accomplishes almost nothing, I have learned to appreciate. One needs to be paying attention, evaluating, and adjusting course all the time. If sometimes the smallness of the steps is challenging and frustrating, it is also rewarding that the activity provides continual and immediate gratification. I have learned much better how to learn.

Over the last several months at the keyboard, I have found the philosophical observations of Robert Nozick very insightful. (Obviously, he hardly had the intention of writing touchy-feely self-help tracts!) He speaks of the function of consciousness as being to evaluate concordance between information coming in various ways. Techniques has many different parts to it. As simple a task as finding a given key may be approached by looking at the keyboard, by proprioception through wrist and shoulders, by imagining where the key is without looking at it, or by feeling it. I have been struck that the errors never involve playing more than one key at a time, but always a wrong key. Our fingers are continually feeling the spaces between the keys and using them to guide motion, without the interstices rising to the level of conscious attention.

Approached as comprehending a bewildering complexity of notes, the task is not possible. One has to hear the sounds before playing them, and bring the body into a position to create them. If your fingers aren't right there when it's time to play the note, they won't get there in time. You have to be positioning your hand to flow from the previous note to the coming one.

…

§ 21

Damit man die Tasten auswendig finden lerne und das Noten-Lesen nicht beschwerlich falle, wird man wohl thun, wenn man das Gelernte fleissig auswendig im Finstern spielet.

So that one can learn to find the keys by heart and the music-reading not be arduous, he will do well if he assiduously practices learned material in the dark.Versuch über die wahre Art das Klavier zu Spielen (Study of the True Art of Playing the Clavier), Karl Philipp Emanuel Bach

I am working to take this point to heart, if not literally keeping the lights out. Lo and behold, little by little it is paying dividends.

© 2026 Paul Nordberg